My Vineyard Year

Sometimes I think there has to be something wrong with a culture in which the "mid-life" crises is so normalized it almost seems like just another stage of life-- like puberty, graduation or marriage. I had casually begun applying the term to myself a few years ago as I found myself in therapy taking a long hard look at how I felt trapped by a constant state of stress from running a farm based business, anxious about how the way I spent my time always felt like a direct choice between my career or my children, resentful about the real challenges of being married to my business partner and creatively stunted because my only outlet for 19 years had been cider and apples.

I wish someone had mentioned the idea of a sabbatical before I had got myself to the point of considering packing my bags and moving to a far away country to run away from myself. But in the strange way that life unfolds, the idea popped into my mind just in time during a phone conversation with a my friend Rick Rainey who was bemoaning the fact that he desperately needed a vineyard manager for his newly planted vineyard.

I've long been excited about what Rick is doing with Forge Cellars. In our many conversations, Rick had expressed a real desire to break out of the status quo of Finger Lakes grape growing as a way to achieve new levels of quality, and especially to move farming practices away the conventional towards a more ecological approach. But the idea of seeing if it would actually be possible to successfully grow vinifera wine grapes organically really captured my imagination.

Traditionally we think of a sabbatical as a paid break from academic work to engage in furthering ones education, but I repurposed the word to fit my own life: employment in the wine industry would give me a break from being self employed and expose me to skills and ideas both different from and relevant to what I already know about growing apples and making cider.

My sabbatical year started out with pruning 17,500 vines at the Forge vineyard located on a site I have affectionally named Windy Ridge. "Windy Ridge" is an under statement...up on Matthews Road, facing just slightly northwest, with the Seneca Lake glimmering below the wind just howls.

Pruning vines is much simpler and formulaic than pruning apples; the plant fruits on 1 year wood, and nearly every bud on a cane will make a cluster or two. So the thought process is; balancing the vine for the current year's fruiting, setting up the vine to grow next years fruit this year, and always thinking about the structure of the vine--the trunk, renewing the trunk, keeping the form of the trunk neat and tidy for an effective Vertical Shoot Positioning (VSP) production system. Once the concept is internalized, the main challenge is to go fast. To prune with out thinking. With young vines in a high density spacing I could prune in the range of 75 vines per hour for 9 hours a day but at night my hands burned with the incessant nerve pain of repetitive motion stress.

Just like with apples, there is no playbook for growing wine grapes organically in the Northeast. What an adventure! With help from my friend Mike Biltonen, lots of reading and the experience of transitioning my orchard to organic tucked away in my mind, I developed a plan for the vineyard. Rick and I established early on that the goals of the season would be: 1.) realize a crop, the first for this 3-year-old vineyard, and 2.) try a biointensive, organic program to see if it was at all possible. It felt a bit like jumping off a cliff into a swimming hole that was obscured by mist. A leap of faith?

My year at Forge was a combination of steep learning curve combined with educated guessing and lots of risk taking. At the heart of this adventure was Phil Davis, my mentor. A second generation grape grower, professional logger and unashamed hippie. Phil generously taught me how to prune, shoot thin, cluster thin and leaf pull. But ultimately, what Phil really gave me was a shared sense of spirituality towards grape growing. I have always felt that farming can be an inherently intuitive practice of having a relationship with plants built on respect and gratitude. But I've often felt alone in a world of agriculture hell bent of efficiency and production. And here was Phil, telling me that this type of intuitive farming was, in fact, the path toward making the greatest wine. This was the medicine I had been looking for.

A lot of people have been asking me: "which fruit is harder to grow, grapes or apples?" I would say that they are hard in different ways. Grapes are formulaic but fussy. The horticulture is relentless. As soon as you finish pruning, you must start tying. Shortly after you finish tying, it's time to start shoot thinning. Then it's time to cluster thin, followed by leaf pulling, followed by pastillage. Soon it's time to pull down the bird nets and then pull them up again on the day of harvest. All the while, the vines face threats of disease...I sprayed every 7-10 days for 5 months!

Apples have lots of disease pressure too, but some of the diseases are only cosmetic. Unlike grapes, the apples don't turn to mush and rot just before harvest. Pruning requires a more complex line of thought since the tree fruits on second year wood, and balancing the tree requites an understanding of vegetative vs. fruitful wood. Apples have dozens of serious insect pests while grapes essentially have two. But it the end, both are perennial plants adapted to a forest edge ecology. Both have deep roots, long lives and the potential to grow very different fruit on different sites and with different styles of management.

At Forge we constantly tasted wine. We tasted it with food. We tasted it with out. We talked about the producers and the way they farmed. We talked about the sites they grew their grapes on. We talked about the region, the culture, the environment.

One of the aspects of my sabbatical that I loved the most was being a part of a community that is focused on making something beautiful. I had become so disillusioned with the cider industry. I felt I was the lone kook ranting on about how the way we grow apples affects the quality of the cider in a room full of people who insisted there was absolutely no connection between yield and quality. You've succeeded as an apple grower when you harvest 1,500 bushels of large, blemish free fruit per acre. If you don't like what that does for your cider, add hibiscus and dry hop it.

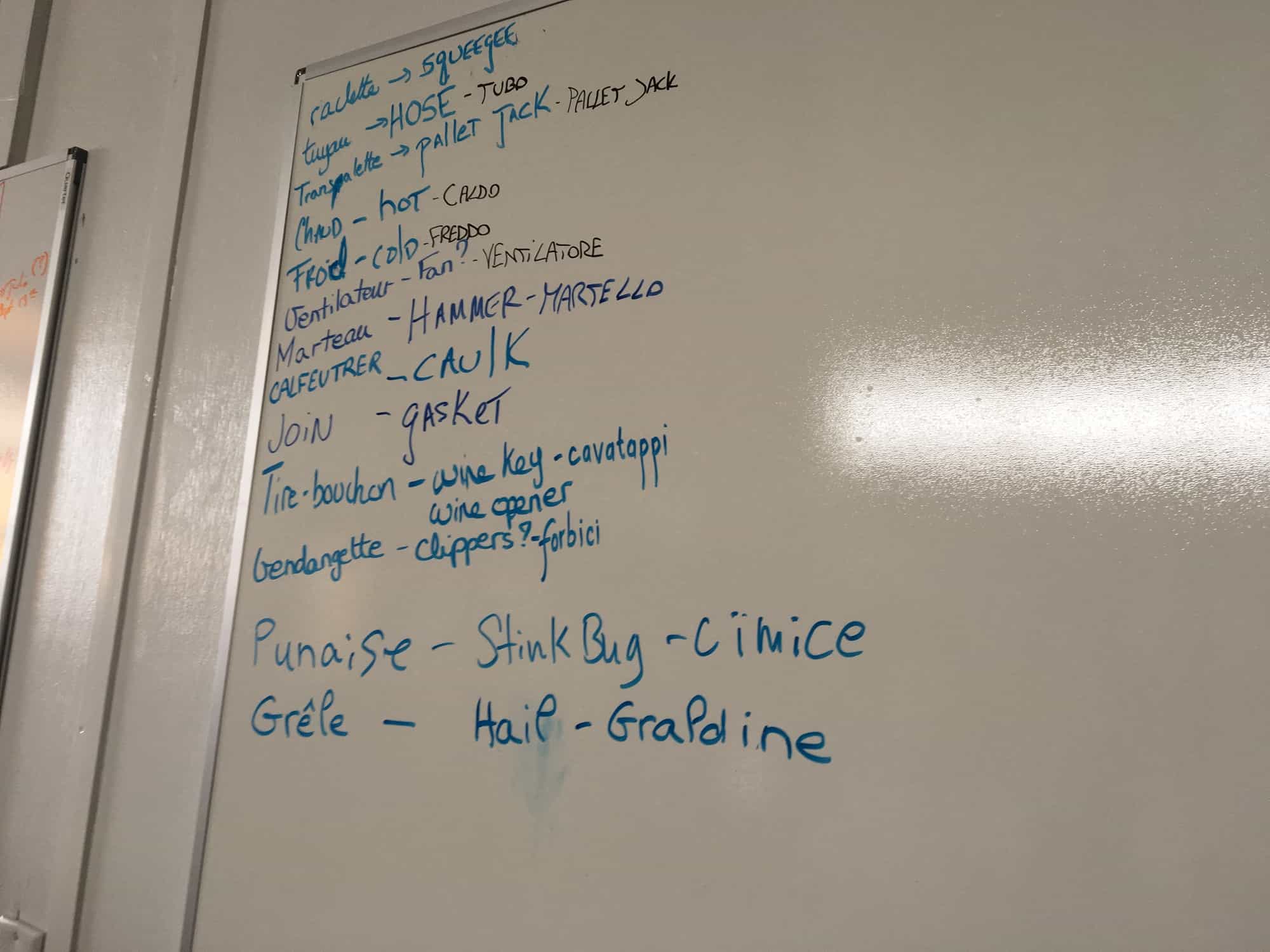

And the people at Forge were wine people to the core. Here's Julia, transplant form New York City where she worked for Terroir Wine Bar. Julia is game for almost any vineyard or winery task. Julia is also a sharp taster who can almost always nail region and variety on a blind tasting. She has worked the grape harvest all over the world and she speaks Italian which is part of the reason why we had a multilingual harvest.

The other reason, of course, is that Rick's partner, Louis Barroul, is a 13th generation winemaker from Gigondas in the Southern Rhone. And while Forge had a visit from Louis' brilliant intern Lianna for harvest, Chateau St. Cosme had a visit from "the apple farmer" for harvest.

I am so grateful for the privilege of spending time getting to know Louis and the way he works. If you don't already know Louis and his wines, I'll tell you. He's a rock star all over the world for his expressive wines. Deep in a cellar which contains original limestone vats carved out of the hillside by Romans in the 2nd century, you'll find a small crew that works like a well oiled machine. This is natural wine with out the affectation. Everything in the winery was instantly recognizable, the same simple tools and simple techniques we use in our tiny cidery. Everything by hand and yet without the crazed, overworked feel I was so used to. Here, everyone took an hour lunch. Here, the amount of work was just right- a lot got done but it was exactly the amount that could be handled. Every tool had it's place, every task it's technique. Even rolling, stacking and filling barrels by hand was done with astonishing competence and efficiency. I felt at home and yet there was so much to learn.

Louis estate is certified biodynamic. It is little vineyards clinging to terraced hillsides surrounded by forest. It is old vines dry-farmed in limestone. It is an intuitive farming that is built on respect and gratitude.

There is something about being in a place so stunningly beautiful, and tasting wines from that place that are so stunningly beautiful, that changes you forever. It's as if there is a seventh sense, a sense many of us have lost, which is the capacity to sense a place. Yes, it involves smelling the garrigue, the cedars and the mistral. Yes, it involves feeling the way the sun heats up the day and the way the night cools down when the air from the limestone cliffs rolls into the valley. Yes, it's the medieval villages and stunning mountain vistas. But it's also the sum of these that adds up to a sense that tells you to always bring an extra sweater for the evening. It's the smell of creosote, blackberry, and thyme in the wine. This combined with the feeling that the place gives you, an emotion, is why tasting Louis's wine still brings tears to my eyes and a longing for his place.

Every fruit grows in Gigondas. When I arrived in late August, the grapes, blackberries, pears, apples and most of all, the figs, were ripe. I hiked the hills around the estate and found figs like I find apple trees on my farm: figs in the hedgerows, figs in the yard, figs in forgotten orchards grown wild and wild figs growing on the edges of the forest. I ate green figs and yellow figs. White figs and red figs. But my absolute favorite were the figs in the vineyard by the Roman Chapel, Saint Cosme. They were a blackish purple and stuck to the tree so ripe they cracked in the dry, dry sun. My mouth waters to remember their sweetness.

Back in the Finger Lakes, 2018 turned out to be the worst grape year in memory. In August the rain started falling and it never stopped. Forge received several extreme rain events, including 9 1/2" in 12 hours. But worse for the grapes was the constant humidity. The sun almost never came out, and when it did, it only served to make things steamy. All around us vineyards started to fall apart. Fruit was cracking because it couldn't dry out. Botrytis and sour rot set in. The fruit flies went crazy. We had put so much into the little vineyard but as each new rain storm rolled in we began to resign our selves to the inevitable...

But somehow, to our astonishment, the grapes hung on seemingly unscathed. By the time we harvested the Pinot at Forge they were ripe, sweet and black as night. Their tough skins did not crack. There was so little rot we picked them and put them directly into the crusher destemmer with no sorting needed.

In the end, I sprayed one conventional fungicide and one that is close to organic but not OMRI certified. The bulk of the program was not only organic, but bio-intensive. What that means is I only sprayed sulfur once, and used low rates of copper soap (resulting in less than 1/20th of elemental copper being applied) and instead focused on building up biology in the soil and on the plant. We started a small farm scale compost program with grape pommace, local manure, local shredded bark and biochar I made from our vine prunings. We transitioned from an annual tillage system for weed control and graft union protection to a perennial, multi species ground cover both in row and under vine and used compost at the base of each vine for cold protection. We began mineralizing the soil. The process of converting a vineyard into a vibrant, healthy, organically managed farm doesn't happen in one year. Work has to be done upfront before benefits are realized. Soil biology takes years to rebuild. Optimal plant health takes time to achieve.

But what we did achieve at Forge in one year far exceeded my expectations. We proved this kind of farming of wine grapes is possible. Not only possible, but in the worst year for bunch rots, our organic, biological program exceeded many conventional programs with potent designer fungicides in their arsenal. I'm so grateful to have been part of this achievement. What an exciting time. This is the beginning of a shift growing practices in the Finger Lakes grape industry. Conventional farming is a dinosaur. There is a new way forward. Consumers are demanding it. Forge is on the cutting edge of making it happen.

The real excitement though, is here, in the wine made with grapes grown more with intuition than anything else. Young vines with exuberance and generosity made concentrated black fruit in a year of disastrous dilution. Ripe, sweet flavors of strawberry and cassis in a year of unhappy acid. A distillation of intention, hard work, crazy weather, and yes, respect and gratitude.

I can't wait to follow this wine as the vines grow up, reaching their roots deep into the crazy clay of Windy Ridge. To follow them as they make a partnership with mycorrhizal fungi, expanding their access to minerals in the shale. To follow them as they soak in the hot sun of the short summer, ripening in the heat alongside the blackberries and goldenrod. These vines have a story to tell.

Early this month, Ezra and I snuck away to the Berkshires for a gathering of holistic orchardists. In this secluded place, I found myself surrounded once again by a community of growers interested in making something beautiful, and this time it was about apples!

Look at this line up. Kingston Black from Van Etten. Kingston Black from Burdett. Kingston Black from Trumansburg. This is really the first time in the measly 18 years of our existence as a cidery that a tasting like this could have happened. Fine cider is where fine wine was in this country 70 years ago...at the very beginning. I'm so grateful to my sabbatical at Forge for bringing me into the beautiful world of wine and reminding me of the world we can create for cider and what we need to do to get there.

With respect and gratitude,

Autumn Stoscheck

March 25th, 2019