Thoughts on Cider and Reparations

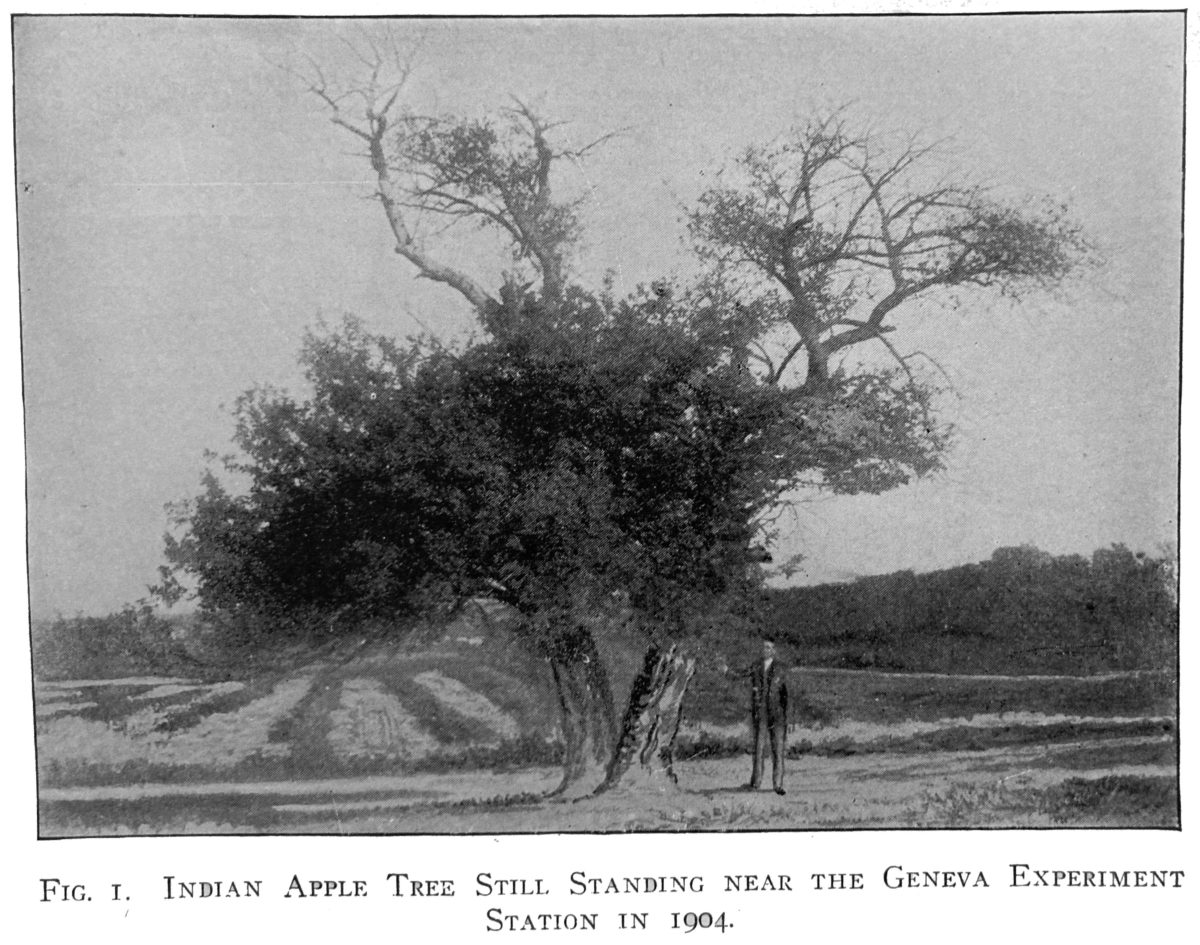

In her 2017 book, The Ghost Orchard (2), Helen Humphreys writes that white settlers made cider from the apples born on the trees that sprouted and regrew from Indian orchards girdled by General Sullivan’s army in 1779. She quotes a resident of Geneva, New York who wrote: “The apple and peach orchards left by the Indians yield every year (an) abundance of fruit for the use of the inhabitants, besides making considerable cider; so much so that one farmer near Geneva sold cider this year in the amount of $1,200” Humphrey’s points out that number was the equivalent of $24,000 in 2017.

Viewed through the lens of colonization, Sullivan’s campaign was not just a military retaliation against the Hodinöhsö:ni’ for siding with the British in the revolutionary war, it was an intentional act of genocide meant to forcibly disposes the people of their land. George Washington ordered Sulivan and his more than 6,200 men (25% of the entire rebel army) that the Indians should ‘not merely be overrun but … be destroyed’. Sullivan’s men burned an estimated 50 villages with 1,200 houses and they also burned over 1 million bushels of corn, countless vegetables and most of the food stored for the coming winter. Additionally, they girdled thousands of apple and peach orchards growing alongside Seneca and Cayuga lakes. (3)

For contemporary cider-making descendants of European immigrants, it’s easy to forget this history, and although road markers scattered throughout the Finger Lakes memorialize some of the major battles, the fact is that most of this history remains hidden in plain sight. The act of foraging for wild apples, of reading the landscape and the stories it reveals, gives us the opportunity to be more than just hipster “natural cider makers” who are getting “in touch” with apples in their “wild state”, it gives us the opportunity to face a history that casts us an awfully unflattering light.

Facing this history gives us an opportunity to face ourselves. Will we merely parallel the white settlers making cider from rewilding Indian orchards on stolen land? Or can we use this history as a way to contemplate and act on righting wrongs? I don’t have an obvious answer but one type of action that has been proposed by Melissa Madden of Open Spaces Cider is building reparations into business models. Some cideries in our region are doing this, Redbyrd Orchard Cider and Black Diamond Cider in the Finger Lakes come to mind. I think it's important to talk openly and discuss these actions-- even though it runs the risk of seeming performative -- because we can normalize making reparations part of everyday life and inspire others into action.

This year, our family gave the total value of $1 for every bottle of cider and perry we made from wild foraged fruit to the Iroquois White Corn Project (4). Iroquois White Corn seeds represent a 1,400 year old relationship between people and plants that cannot be put in a museum. Corn needs to be planted every year, and inspite of genocide, land theft, diplacement, and forced cultural assimilation, seed keepers have kept this corn alive. We honor the deep agricultural knowledge of the Hodinöhsö:ni’ people and support their ongoing efforts at land and seed rematriation.

~Autumn Stoscheck, December 2021

Sources: 1. Beach, S. A. (1905). The apples of New York: By S.A. Beach. Lyon. 2. Humphreys, H. (2017). The Ghost Orchard: The Hidden History of the Apple in North America. HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. 3. Spiegelman, R. (n.d.). Clinton campaign. Sullivan. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.sullivanclinton.com/ 4. About iroquois white corn. Ganondagan. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://ganondagan.org/whitecorn/about.